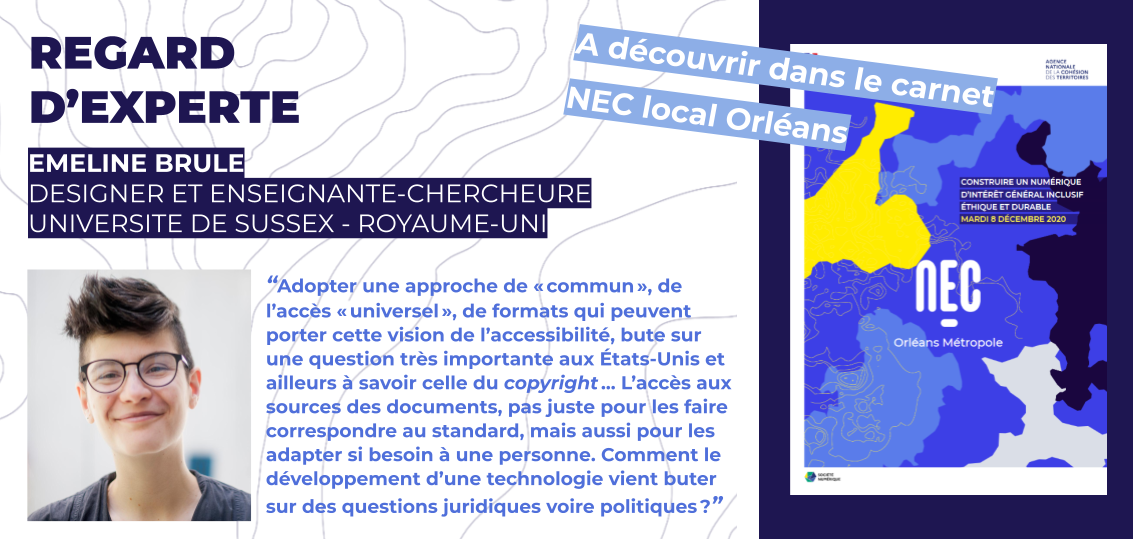

Émeline Brulé is a designer and teacher-researcher at the University of Sussex (UK). Since 2014, she has been working on accessibility and inclusive design issues in the field of Human-Computer Interfaces (HCI). A graduate of Telecom Paris, she worked for several years on the Accessimap research project, which aimed to develop technologies for the accessibility of diagrams and drawings for blind people. She studied the school experiences of visually impaired children in France and the role that digital tools play in them. Her view on accessibility design seems to us to be quite enlightening on many issues facing those who seek to build a digital society that is open, ethical and sustainable, but also inclusive and therefore accessible to all.This interview comes from the notebook produced for the Numérique en Commun[s] Orléans Métropole organized in December 2020 (available online, in "facilitated reading" format and in PDF format).

Émeline Brulé is a designer and teacher-researcher at the University of Sussex (UK). Since 2014, she has been working on accessibility and inclusive design issues in the field of Human-Computer Interfaces (HCI). A graduate of Telecom Paris, she worked for several years on the Accessimap research project, which aimed to develop technologies for the accessibility of diagrams and drawings for blind people. She studied the school experiences of visually impaired children in France and the role that digital tools play in them. Her view on accessibility design seems to us to be quite enlightening on many issues facing those who seek to build a digital society that is open, ethical and sustainable, but also inclusive and therefore accessible to all.This interview comes from the notebook produced for the Numérique en Commun[s] Orléans Métropole organized in December 2020 (available online, in "facilitated reading" format and in PDF format).Références :

Could you introduce us to your investigative work, starting with your interest in the issue of so-called "accessible" design?

Émeline Brulé: Working on so-called "inclusive" or "accessible" design or "accessibility design" goes back to long before I started my thesis. I come from illustration and typography, from the field of books, but also from the web. In this sense, as a young design student, I was interested indigital publishing, in the changes it triggered in the publishing sector and in the set of formats that developed at that time, such as the ePub format standard. This question of formats and standards, of their design and circulation, led me to question myself on the questions of accessibility of contents in a broader sense and to start a PhD in HMI which concerned a project of interactive map for blind or visually impaired people. In doing so, I was able to immerse myself in the history of digital technology and its accessibility for audiences with different forms of disabilities.One of the first milestones in this history was laid by the American researcher Ray Kurzweil, who worked on automatic Braille transcription. He developed optical recognition algorithms that made it possible to scan texts and then translate them into Braille so that they could be accessible to visually impaired people. But adopting an approach of "commonality", of "universal" access, of formats that can carry this vision of accessibility, comes up against a very important issue in the United States and elsewhere, namely that of copyright... Access to the sources of documents, not just to make them correspond to the standard, but also to adapt them if necessary to a person. How does the development of a technology come up against legal and even political issues? But I think these questions arise for all technologies (laughs)...

In any case, on the issues of accessibility, accessibility design and "inclusive" Human-Machine Interfaces, a lot of work comes from the problems of visual impairment. In this research, there is often a tension between approaches that aim at invisibilization or elimination of the disability, for example optical implants for blind people or technologies to replace guide dogs, and approaches that are rather turned towards interdependence, the common.

Accessibility is at the crossroads of scientific disciplines that include psychology, perception, educational sciences, computer science, machine learning research, etc. A crossroads that has the advantage of offering a constantly renewed research topic. And I really like being at this crossroads, being able to investigate with the tools of ethnography on social issues, particular groups, and then develop digital tools. This is what I did in the Accessimap project: I investigated at the Centre d'Education Spécialisée pour Déficients Visuels Institut des Jeunes Aveugles de Toulouse (CESDV-IJA) at the same time as I developed prototypes of interactive maps, and worked with professionals to develop activities with tangible technologies but also using the rest of the senses, smell, taste, etc.

So this "handicap" approach is something that is of great concern to the world of Human-Computer Interfaces?

Émeline Brulé : Yes, absolutely. In 1964, a community of blind developers developed and formed a committee(Committee on Professional Activities of the Blind) at theAssociation of Computing Machinery to encourage accessible employment in this sector. But blindness is also a very "interesting" issue for engineers, it is at the crossroads of many interests found in computer science: the question of perception, that of its processing, that of automatic data adaptation, etc. The question arises with each new generation of technologies. For example, digital manufacturing, on which I have worked a lot. With 3D printing in particular, a whole field of research has developed around the possibility of creating unique and personalized artifacts in fablabs, for example for teaching. The interest came from the fact that the technologies are less expensive: parents could, for example, train themselves in modeling and then in 3D computer manufacturing, in laser cutting to make representations for their children. Some research is looking at automatic modeling by simplifying images or 3D models. But this being said, the problem is far from being solved, we must not fall into the utopia of believing that technology will solve everything, that education is only a question of access to information... I am also against a computer model capable of repairing or making the handicap disappear so that it does not bother us too much, so that we can automate learning as much as possible, eliminate human accompaniment, etc.From an ethnographic point of view, when I was working at the Institut des Jeunes Aveugles in Toulouse, I realized that it was the tinkering with and around technology, by teachers, staff and the children themselves, that is the most interesting when we try to understand the most effective ways of learning. There is no such thing as a single, universally accessible technology; it must be adapted, tinkered with each time to suit each child who is visually impaired or blind. In fact, accessibility is also at this point: in the capacity that a technology offers to its user to be modified, adapted to other uses. But unfortunately, thinking about technologies in this way means, for example, upsetting the idea that everything can be scaled up and universalized, which is one if not the main motivation behind the deployment of IT in education...

So there is an important difference between accessibility and inclusiveness?

Émeline Brulé: Yes, we are not talking about the same thing. Making things "accessible" is above all a standard to be reached: door sizes, worktop heights, access ramps, elevators, easily navigable websites for visually impaired or blind people, etc. But in doing so, we forget the singularities of each person and we have rules that are, in the end, sometimes restrictive even for the blind. But in doing so, we forget the singularities of each person and we have rules that are, in the end, sometimes restrictive even for people with disabilities. The example of California is interesting on this point: when it was urbanized, at the end of the second world war, we have infrastructures related to accessibility such as roads and sidewalks that could be much wider which seem remarkable. But that model was designed only for the disabilities of people who were in wheelchairs and using their cars. The problem is that for many people, it is not at all easy to take the car... And this infrastructure developed around the personal vehicle, well, it is not inclusive of children, poor people, not inclusive of elderly people, blind people, etc.How do you think focusing on the inclusion of visually impaired or other types of disabilities better addresses the question of what we really want to do with technology?

Émeline Brulé: Working on this question allows us, in my opinion, to think about technologies in particular from the point of view of their sustainability and human rights: there is an obligation of accessibility to which technologies only partially respond, we have to think about everything that surrounds them, how they are taught, maintained, whether they are really useful or add too much cognitive load, etc. This often leads us to the question of the frugality of technologies and their sustainability, but in any case, thinking about technologies so that they are as inclusive as possible allows us to put them truly at the service of people, not to be afraid to use them. This often brings us to the question of the frugality of technologies and their sustainability, but in any case, thinking about technologies so that they are as inclusive as possible allows us to put them truly at the service of people, not to invent uses because of them. This allows us to build on the longer term, so that technology helps us to live better, to improve the common good.I also believe that there are several ways of thinking about accessibility and that they are not all at the same level. In the video game industry, for example, there is a lot of work being done on these issues: games are now much more configurable. There is also a lot of work on controlling video games with movements, particular gestures, etc. All these efforts are very good for experienced gamers, but for beginners, the thing becomes complicated. Managing this complexity is the biggest challenge for HMI researchers: how to make complex tools accessible without hindering more expert uses, or a progression towards more expert uses?

I believe that we should simply offer users a choice: allow them to adapt the interfaces to their uses. From that point on, stronger forms of individual adaptation may appear. But this pushes us to rethink our relationship with disability, to think of it as something that must have a place in our organizations.

What you are saying here makes me think of a concept that is currently being discussed in France, with a lot of misunderstandings about it, and that is that of intersectionality. In what you are saying here, and drawing a parallel to the topic we are investigating with the NEC notebooks, I am hearing that issues of digital exclusions must also be analyzed through the prism of several types of exclusions. In other words, these digital exclusions must be analyzed at the intersection of several types of exclusions, of discriminations.

Émeline Brulé: Absolutely, and I think we have a problem in France with identifying these discriminations, these exclusions and their intersections. It is complicated to have figures on these issues, for example how social class impacts the rate of disability in children and their schooling, and yet I believe that it is by crossing these different data that we can concretely see geographical areas, sections of the population to be helped more than others. Poor people, people from immigrant backgrounds, people with disabilities, people living in disadvantaged areas are, for sure, terribly concerned by the problems related to digital exclusion, or at least to a difference in opportunities. To take a very concrete example: Apple devices are generally considered more accessible, both individually and because they are easy to use together. However, they are more expensive! So when you have on the one hand a blind teenager, coming from a rather comfortable family, who is encouraged every day to develop his mastery of computer tools, and who has a strong support to use them wisely, but on the other hand disadvantaged teenagers who are lent cheaper equipment, locked to avoid any unexpected use... They don't start out equal.