Geneviève Fontaine is a project manager at the Godin Institute and director of the TETRIS research center - Territorial Ecological Transition through Research and Social Innovation. She holds a doctorate in economic and social sciences. Her research focuses on the intersection of solidarity economy, social innovation, commonalities and the capability approach to sustainable development.

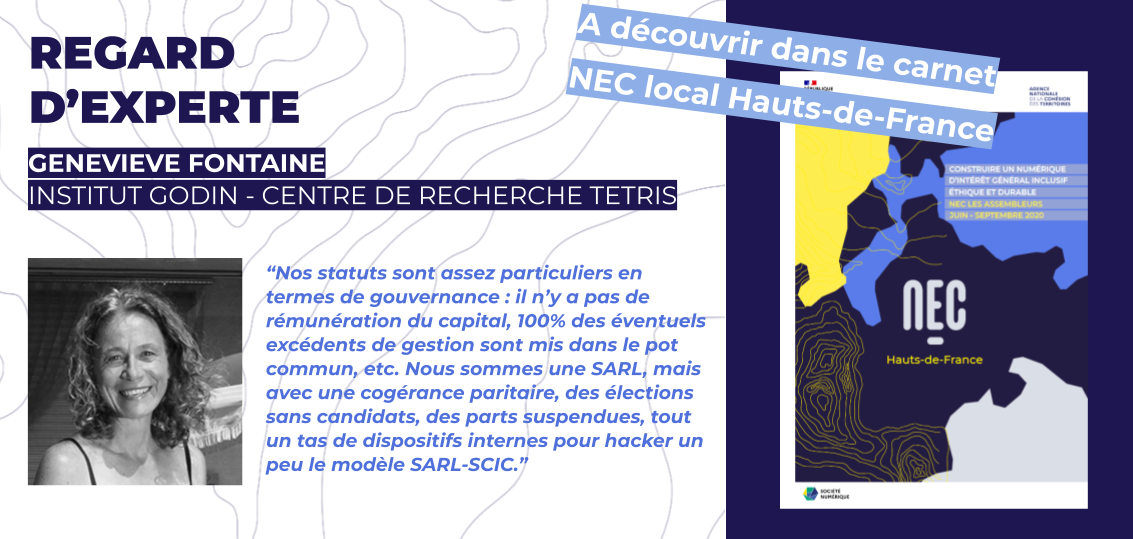

Initiator of the Territorial Pole of Economic Cooperation (PTCE) TETRIS located in Grasse (Alpes-Maritimes department), she leads and coordinates the center of applied research and multidisciplinary transfer which structures this PTCE. But TETRIS is also a third place where we discuss popular education, social and solidarity economy, social innovation, but also "commons" and "capabilities". In this interview, we look at some of these notions.This interview is taken from the notebook produced for the Numérique en Commun[s] Hauts-de-France organized between June and September 2020 by the Assemblers (available online, in "facilitated reading" format and in PDF format).

Where do you start when you want to present your background and what you do?

Geneviève Fontaine: To begin with, I would like to say that I am an associate professor of economic and social sciences and that I was a teacher in a high school at the end of the 1990s with a strong desire to work on issues of sustainable development and education. What I wanted to do at that time was to reflect, with my colleagues and students, on capabilities, based on Amartya Sen's approach to sustainable development. In doing so, we created a high school club, then an association, then the TETRIS collective interest cooperative, always with this desire to equitably develop collective capabilities on a territory. Since then, I have been leading the research part of this cooperative, and I did an economics thesis on this project, crossing the sustainable development capabilities approach with Elinor Ostrom's commons approach. I am doing research, notably at theGodin Institute in Amiens, for a position based in Grasse at the Sainte-Marthe third place and I work on societal transformations so that they are democratic, sustainable and inclusive.What interests me is to see how, in a project of third places, there can be a dialogical tension between the digital transition, which is moving forward without really knowing where it is going, and the ecological transition, which knows where it wants to go, but does not know where to go. This is the reason why I am working today on "digital", which I consider to be a key competence of sustainable development, but which I wish to question in order to understand where it is useful and where it is not. I am an activist for sustainable development, an activist for third places and then a researcher embedded in a third place which is a young university enterprise and which is a privileged space of investigation on the modalities of sustainable, inclusive, fair and democratic transformations of our society.

Why and above all how did TETRIS become a Cooperative Society of Collective Interest (SCIC)?

Geneviève Fontaine: Concerning the TETRIS project, you should know that we have been talking about third places since 2008. At the beginning, there was an association called Evaleco which tried to decompartmentalize the worlds of popular education, education for sustainable development and the solidarity economy in a given territory. And the first thing that stands out in our project is that we took a real estate risk: taking premises and very quickly opening them up to everyone, to all the militant dynamics and citizen groups. This project was very quickly "filled", it was very quickly full of people, full of dynamics. It proved to be very interesting in a local universe where the words citizen, popular, are often words that do not exist in acts in public policies... And it is rare enough to notice it, to understand that it is a risk: in Grasse, the municipality does not have land, there is no access to rooms for associations, at least very few, and it is for this reason that we made a third place very quickly.It also happens that we were able to get people on board very quickly, maybe because we came from a high school and there were technical courses inside and we were able to enroll a whole bunch of students who came to build a fablab in their own way and from 2010 onwards inside this place that we were opening.

A few months later, we changed location, we tripled our surface area by setting up a transitional project in premises that were to be demolished two years later with a plot of land, a shed. As a result, we joined other collectives, around the bicycle, the garden, etc. And it is because it aggregated like that that the community came to see us in 2012 when it launched a policy of support to the SSE and asked us to launch a territorial pole of economic cooperation. Once this PTCR was set up, we realized that we had to continue taking risks, that we needed an even bigger place because the reception we were setting up was constantly expanding. Strangely enough, the worlds with which we had the fewest links at the time were those of culture, whereas we worked a lot with those of social action, of solidarity with migrants, with parishes, with mosques... We were, however, militants of popular education and secularism [laughs]... But it is by doing, by doing together that we develop, it is on this doing that we aggregate the dynamics and that we learn to make a third place.

The image of a SCIC, its set up allowed us to be more "serious", to get out of the image of a militant association of sustainable development. It became a complementary "legal vehicle", a way to protect the members of the association's board who were taking a lot of risks by following us on risky real estate projects. So we created a commercial company for these reasons and to allow Evaleco to find its freedom of militancy and to carry out more consequent real estate projects. The legal framework that allowed us to be on the same level as the local community in terms of decision making, well the SCIC was the obvious choice. Our statutes are quite particular in terms of governance: there is no remuneration of the capital, 100% of the possible management surpluses are put in the common pot, etc. We are a limited liability company, but with a legal status that allows us We are a SARL, but with a joint management, elections without candidates, suspended shares, a whole bunch of internal devices to hack the SARL-SCIC model a bit.

And did you develop in terms of engineering of legal assembly SCIC, your model of governance in other words, influenced actors who attended the third place Sainte-Marthe?

Geneviève Fontaine: Not really, in fact it allowed us to sort things out... At the beginning, there was a great confusion between the SCIC and the third place, people believed that it was necessary to be a member to carry out activities in the third place. The first local project that we had aggregated a lot of structures and we were able at that time to work on the will that we had to create a common land: to set the rule where the rent paid does not depend on the occupied square meters, but on the contribution to the collective project. We presupposed that it was possible to build a common like that. But we had stowaway phenomena that changed that, we saw enclosures develop in the place. As a result, TETRIS found itself with a very high rental debt. But we held on, because the members wanted to continue, their DNA was to be a third place.A little later, in 2018, after agreeing on ways to repay this debt, we found a new site to install our third place, a former school managed by a religious congregation who preferred our project to those carried by the city hall, the clinic next door, etc. We were entrusted with this site, because the congregation believed in our capacity to take care of this place. It's not a lease, it's a commodat for an unlimited period of time and this congregation is now part of our project, takes part in the decision making of this project which is not economic, but does not reject it. It is a place of experimentation, of research around the question of the ecological transition, a place that allows to try and that goes from popular education to fundamental research. It is a place where we can really live, a place where we never stop working on this initial idea, which has never changed, and which is to work on capabilities and sustainable development. This place has become a common ground to be nourished, to be built, a collective project to be taken care of.